My video “Oboe Players Are Movers!” was created out of frustration. Too many good teachers tell students that to become a great oboe player, one should not move. I’m frustrated hearing this because I’ve seen the unfortunate result of this maxim: good students, who are just trying to do what they have been told, grow into mature players who are very stiff. Arms rigid, faces immobile, breath constrained. They seek my help, wanting to figure out why they are in such pain. Well, the fact is that years of resisting free and healthy movements can lead to injuries such as tendonitis, or TMJ syndrome, or spinal injuries. The subconscious mantra not to move may also limit the ability to play highly technical passagework, or to meet the challenges of breathing.

The good news is that the tide seems to be changing. More and more I’m running into teachers and students who acknowledge that movement is good, and who actively seek ways to move better in order to make better music.

But recently I ran across yet another example of that outdated mode of teaching, which advocated playing the oboe with a static stance. The DVD set of master classes given by John de Lancie, former Principal Oboist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, entitled “The Art of Creating the Musical Line” contains many gems of wisdom about playing music and playing the oboe. But it also includes an amazing exchange between him and a young Krista Riggs (transcribed below), in which he repeatedly admonishes her not to move.

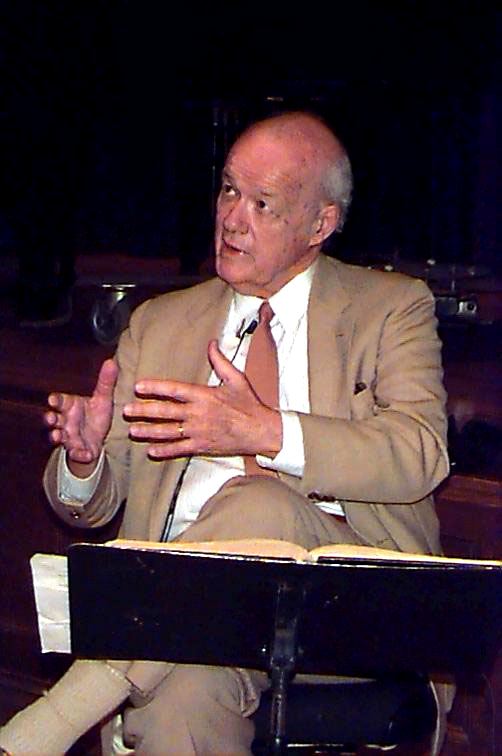

Now don’t get me wrong, I have complete respect for Mr. De Lancie (pictured above). As a beginning oboe student, I idolized many of his recordings including the Satie Gymnopedies and the Francaix Flower Clock, a work written for him. Much later I served as his colleague on the faculty of the Las Vegas Music Festival. I enjoyed getting to know him personally, and admired his work with our students. Today, many of America’s top oboe performers and teachers are former students of John de Lancie.

In the lesson with Krista Riggs, he is correct to object to the rhythmic pulsing she is doing. It is interfering with the musical line, slightly upsetting her embouchure, and visually distracting. I run across many students who have this issue, and it can be challenging to find a means for the student to undo this negative habit.

However, it is the manner Mr. De Lancie goes about trying to “help” Krista (who otherwise plays quite nicely during the lesson) that I find problematic. And the words he uses are very much reflective of his time—a time when music pedagogy did not put enough importance on properly understanding and training movement.

As you read the transcript of this part of the lesson, notice how often he says, “don’t move.” At one point he literally just repeats that phrase three times in a row! So instead of Krista receiving the message that rhythmical movements are distracting and can disrupt the musical line, she only hears, “don’t move!” Instead of telling her that it is better to internalize the rhythm so you don’t express it with your body (and that by doing this you can make your body more available for all the other movements needed to play well), we hear, “don’t move!” Instead of warning that one must be careful to use appropriate movements that don’t interfere with the delicate balance of the reed against the embouchure, one only hears the warning: “Try not to move…’cause when you don’t move, it sounds better.”

Read the transcript below, and see if you don’t agree with me that there needs to be a better way to discuss these movement issues. This need is the reason I created my video, and it is the reason I wrote my book, “Oboemotions.” Oboe players must move in order to make music. All musicians are MOVERS. And because we are movers, we must learn to train movement accurately.

TRANSCRIPTION FROM DVD “The Art of Creating the Musical Line”— The Barret Master Classes, Volume Five

John de Lancie to Krista Riggs: “You gotta’ break that habit of beating time. When you move around…you know, it’s tough enough to play the oboe, and when you’re moving around you cannot help but change a little bit…in your…the way your reed is in your mouth, and so on and so forth. If you just try…I recommend practicing standing up against a wall and…Actually, uh, I found that practicing up against a wall creates a sensation that, that I can’t, I’ve never been able to find in any other way. If you’re standing up against a wall and nothing moves…it’s, it was the, I remember that it was the first time and the only time that I ever almost had the impression that I was listening to myself—that I was standing out, listening to myself. And you just think: Nothing is gonna’ move, but your music. You HAVE to move your fingers, but DON’T move anything else. And just see if you can be as quiet as possible, and listen.”

(later, as she begins to play) “Yeah, but you see your oboe going up and down? Alright, see if you can STOP that…that’s very important.”

(as she plays again) “Don’t Move! Don’t move, don’t move.”

(later) “Let’s try it once more, huh? Try not to move. Try not to move. Try not to move. ‘Cause when you don’t move, it sounds better.”

Post Script:

Krista Riggs developed into a very fine oboist. She completed a Doctorate in Oboe Performance from Indiana University, and went on to teach oboe at Fresno State University in California. I sent a copy of this blog and transcription to Krista Riggs for feedback. Here is part of her response:

“Of course it’s fine to use this transcription! It brings back memories. That was a long time ago! I often received similar feedback from various coaches and teachers, and ‘not moving’ felt very unnatural and almost like being in a straight jacket. Sadly I’m not able to play oboe anymore due to trouble with my spine, so I’m a bit removed from that world now.”